January 29, 2026 – If you’ve been building with AI for the past few years, you’ve probably spent countless hours crafting the perfect prompt. Finding exactly the right words, the right examples, the right tone to coax your language model into doing what you need. That era is ending.

The conversation in AI development has fundamentally shifted from “prompt engineering” to something broader and more powerful: context engineering. In July 2025, Gartner explicitly declared: “Context engineering is in, and prompt engineering is out.” Anthropic, the company behind Claude, now describes context engineering as “the natural progression of prompt engineering.” Tobi Lütke, CEO of Shopify, calls it “the art of providing all the context for the task to be plausibly solvable by the LLM.”

This isn’t just rebranding. It represents a fundamental evolution in how we think about building AI systems. As AI applications have grown more sophisticated moving from simple text generation to complex agents that reason across multiple steps, use tools, and maintain long-running workflows the limitations of prompt engineering have become clear.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore what context engineering actually is, how it differs from traditional prompt engineering, the technical challenges it addresses, core strategies for implementation, and why mastering this discipline has become essential for anyone building production AI systems in 2026.

Understanding the Shift: From Prompts to Context

To understand context engineering, we first need to recognize what changed and why.

The Prompt Engineering Era (2020-2024)

When GPT-3 launched in 2020, followed by ChatGPT in late 2022, the primary challenge facing developers was learning how to communicate effectively with language models. This gave birth to prompt engineering the practice of crafting specific instructions, examples, and phrasing to elicit desired outputs from AI models.

Prompt engineering focused on questions like:

- How should I word this instruction?

- Should I use few-shot examples or zero-shot?

- What temperature and sampling parameters work best?

- Should I use chain-of-thought prompting?

For simple, single-turn tasks classification, summarization, short-form generation prompt engineering worked remarkably well. A cleverly worded prompt could dramatically improve output quality.

The Limitations Emerge

As developers began building more complex applications, they encountered fundamental limitations:

Context Window Constraints: Early models had 4K-8K token limits. You couldn’t fit everything you needed in a single prompt.

Multi-Step Workflows: When AI agents needed to complete complex tasks requiring multiple steps, tools, and decisions, a single prompt couldn’t capture all necessary information.

Dynamic Information Needs: Different tasks required different background information. A static prompt couldn’t adapt to changing requirements.

Information Overload: Flooding the context with all possible information diluted important details and degraded performance.

Stateful Interactions: Long-running conversations or workflows needed to maintain state across multiple interactions, something prompts alone couldn’t handle.

The realization crystallized: the words you use matter less than the information environment you create around the model.

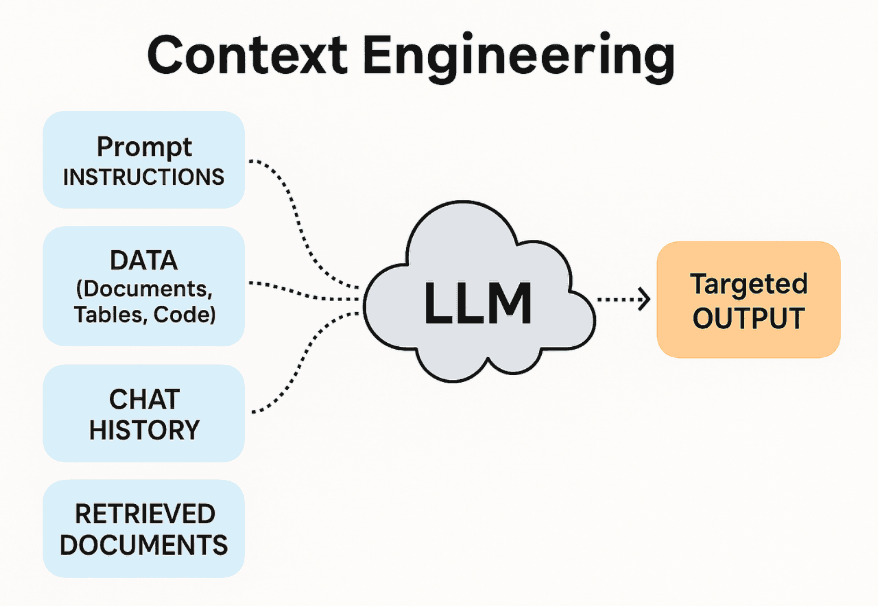

What Context Engineering Actually Means

Context engineering is the practice of designing and managing the complete information environment that a language model operates within during task execution. This includes everything the model “sees” when generating a response:

- System instructions and behavioral guidelines

- Retrieved documents and knowledge bases

- Conversation history and prior interactions

- Tool definitions and API schemas

- Environmental state and metadata (current time, user information, session data)

- Examples and demonstrations

- Structured data from databases or APIs

- Real-time information from external sources

Rather than focusing narrowly on how to phrase a request, context engineering asks: What should the model know, when should it know it, and how should that information be structured?

The Technical Foundation: Why Context Matters

Understanding why context engineering matters requires understanding how language models actually work at inference time.

The Context Window: Fixed Budget, Unbounded Needs

Every language model has a context window a fixed token limit for all information it can consider when generating a response. Modern models have expanded these significantly:

- GPT-4: 128K tokens (~96,000 words)

- Claude 3: 200K tokens (~150,000 words)

- Gemini 1.5 Pro: 2M tokens (~1.5 million words)

While impressive, these limits are fixed. Meanwhile, real applications generate unbounded information:

- An AI coding assistant might need to reference an entire codebase (millions of tokens)

- A customer support agent accumulates conversation history over hours

- A research assistant processes dozens of documents

- A workflow agent makes 50+ tool calls, each generating context

Without deliberate management, you face an optimization problem: what information gets included, what gets excluded, and how do you make those decisions effectively?

Context Rot: The Performance Degradation Problem

Recent research has revealed a troubling phenomenon called “context rot” the degradation of model performance as context length increases, even when well within the stated context window.

A landmark study analyzing 18 leading LLMs (including GPT-4, Claude 3, Gemini 1.5, and others) found:

- Performance doesn’t decline linearly with context length

- Degradation patterns are unpredictable and model-specific

- Simply having a large context window doesn’t guarantee good performance across that entire window

- Critical information can be “lost” even when technically present in context

This means that more context isn’t always better. Effective context engineering requires understanding not just how much information to include, but how to structure and prioritize it.

Core Principles of Context Engineering

Effective context engineering rests on several fundamental principles:

1. Context Is Dynamic, Not Static

Unlike prompt engineering, where you might craft a single prompt template, context engineering treats context as the output of a dynamic system that runs before each model call.

Context should be:

- Constructed on-the-fly based on the current task

- Tailored to specific user needs and situations

- Adaptive to what the model needs at each step of a workflow

2. Selectivity Over Completeness

The goal isn’t to give the model access to all possible information. It’s to give it exactly the right information for the current task.

A focused 300-token context often outperforms an unfocused 113,000-token context for specific tasks. Quality and relevance trump quantity.

3. Structure and Format Matter

How you present information is as important as what information you present:

- A concise summary often works better than raw data dumps

- Structured formats (JSON, tables, bullet points) improve model comprehension

- Clear tool schemas enable better decision-making than vague descriptions

- Logical organization helps models navigate complex information

4. Tools Are Context

When building AI agents, tool definitions and their outputs become part of the context. Well-designed tools that return token-efficient, relevant information enable better agent behavior than poorly designed tools that return verbose, unfocused data.

5. Continuous Curation Is Required

Context management isn’t a one-time decision. Long-running applications require continuous curation—deciding what stays, what goes, what enters, and when throughout execution.

The Four Core Strategies for Context Management

Based on research from Anthropic, leading AI labs, and production systems, four fundamental strategies have emerged for effective context engineering:

Strategy 1: Externalization (Don’t Make the Model Remember Everything)

The foundational principle is simple: persist critical information outside the context window where it can be reliably accessed when needed.

Implementation Approaches:

Scratchpads: Dedicated storage spaces where agents write notes and observations during execution. Just as humans jot notes while solving complex problems, AI agents use scratchpads to preserve information for future reference.

Example: An agent researching a topic writes key facts to a scratchpad after each search. Later steps reference the scratchpad rather than re-searching or relying on potentially truncated context.

Vector Databases: Semantic storage systems that allow models to retrieve relevant information based on similarity rather than exact matching.

Example: A customer support agent with access to thousands of support articles uses vector search to retrieve only the 2-3 most relevant articles for the current issue, rather than including all articles in context.

Structured External Memory: Databases, key-value stores, or file systems where information is explicitly saved and retrieved as needed.

Example: A project management agent saves task lists, deadlines, and status updates to a database, querying only relevant information for each decision point.

Strategy 2: Summarization (Compression Without Losing Meaning)

When information must remain in context but takes too much space, intelligent summarization reduces token usage while preserving essential meaning.

Implementation Approaches:

LLM-Powered Summarization: Using the model itself (or a specialized smaller model) to condense information before adding it to context.

Example: After every 10 conversation turns, use an LLM to create a 200-token summary of key points, decisions, and context, then replace those 10 turns with the summary.

Hierarchical Summarization: Creating summaries at multiple levels of granularity detailed summaries of recent context, broader summaries of older context.

Example: Keep detailed context for the last 5 interactions, medium-detail summaries for the previous 20 interactions, and high-level summaries for everything older.

Agent-to-Agent Handoffs: Companies like Cognition AI use fine-tuned models specifically for summarization at agent boundaries, ensuring critical information transfers efficiently between different parts of a system.

Strategy 3: Trimming and Pruning (Strategic Removal)

Rather than intelligent summarization, trimming uses heuristics to remove context based on rules:

Implementation Approaches:

Recency-Based Trimming: Keep the N most recent messages or interactions, discard older ones.

Importance-Based Filtering: Assign importance scores to different pieces of context, keeping high-importance items and discarding low-importance ones.

Task-Specific Pruning: Remove context elements that aren’t relevant to the current task type.

Example: When switching from a data analysis task to a writing task, prune all the statistical data and code execution results that were relevant for analysis but unnecessary for writing.

Trained Pruners: Specialized models trained to identify which parts of context can be safely removed without hurting performance. Research systems like Provence have demonstrated effectiveness in question-answering tasks.

Strategy 4: Isolation (Different Information for Different Tasks)

Rather than cramming all information into a single context, isolation techniques partition context across specialized systems.

Implementation Approaches:

State Object Isolation: Design agent runtime state as a structured schema with multiple fields, exposing only relevant fields to the LLM at each step.

Example: An agent might have fields for message_history, user_profile, active_tools, and session_metadata. For a simple query, only message_history is shown. For a complex task requiring personalization, both message_history and user_profile are included.

Multi-Agent Architectures: Split tasks across specialized agents, each with focused context for their specific domain.

Example: Instead of one agent handling everything, use a “research agent” with access to search tools and document context, a “writing agent” with access to style guidelines and templates, and an “orchestrator agent” that coordinates between them without needing all their specialized context.

Task-Specific Context Windows: Maintain separate contexts for different types of tasks, switching between them as needed.

Advanced Techniques and Patterns

Beyond the core strategies, several advanced patterns have emerged from production systems:

Context Allocation Budgeting

Deliberately allocate your context window across different needs:

- System instructions: 2,000 tokens

- Conversation history: 10,000 tokens

- Retrieved documents: 20,000 tokens

- Tool schemas: 5,000 tokens

- Real-time data: 3,000 tokens

This ensures critical information always has space and prevents any single category from dominating context.

Semantic Compression

Instead of preserving verbatim text, extract key facts and relationships, storing them in a compressed semantic format.

Example: Rather than storing “The user mentioned they prefer meetings in the morning and don’t like afternoon calls,” store structured data: preferences: {meeting_time: "morning", call_time: "not_afternoon"}.

Proactive Context Management

Instead of reactive context management (responding when limits are hit), proactively structure context from the beginning.

Techniques include:

- Pre-filtering documents before retrieval

- Generating summaries as information is collected rather than waiting until context is full

- Structuring multi-step plans to minimize context accumulation

Memory Hierarchies

Implement multiple memory tiers with different retention and access patterns:

- Working Memory: Current context window (highest priority, most accessible)

- Short-Term Memory: Recent session information (readily retrievable)

- Long-Term Memory: Historical information stored externally (searchable, selectively retrieved)

Context Folding for Long-Horizon Tasks

For agents executing complex, multi-step plans:

- Allow agents to “branch” their execution, retaining full context within the branch

- After completing the branch, return to the main execution path with only a self-chosen summary

- This enables deep exploration without permanently expanding context

Research from systems like AgentFold demonstrates this approach enables long-horizon tasks that would otherwise be impossible.

Practical Implementation: A Real-World Example

Let’s walk through a concrete example of context engineering for a research assistant agent:

The Task: Help a user research and write a comprehensive report on renewable energy trends.

Without Context Engineering:

- Dump all search results into context

- Include full conversation history

- Add all tool definitions simultaneously

- Context quickly fills with redundant information

- Performance degrades as irrelevant data accumulates

- Agent loses track of what’s important

With Context Engineering:

Step 1 – Query Understanding:

- Context: System instructions + user query + user profile (preferences, writing style)

- Agent generates search plan

- Output: Structured plan stored externally

Step 2 – Research Phase:

- Context: System instructions + current search query + previously found key facts (from scratchpad)

- Agent searches and extracts relevant information

- Each finding written to external scratchpad

- Search results themselves not kept in context (only extracted facts)

Step 3 – Organization:

- Context: System instructions + accumulated facts from scratchpad + outline tool schema

- Agent organizes findings into structured outline

- Outline stored externally

Step 4 – Writing:

- Context: System instructions + current section outline + relevant facts for that section only

- Agent writes one section at a time

- Previous sections not included in context (already written and saved)

Step 5 – Review:

- Context: System instructions + full draft (summarized) + user preferences

- Agent reviews for coherence and completeness

- Suggests refinements

This structured approach keeps context focused, relevant, and manageable at each step, enabling the agent to complete a complex, multi-hour task that would otherwise fail due to context overflow or degradation.

Tools and Frameworks for Context Engineering

Several tools and frameworks have emerged to support context engineering:

LangChain and LlamaIndex: Provide abstractions for memory management, retrieval, and context structuring.

Vector Databases: Pinecone, Weaviate, Qdrant, ChromaDB enable semantic storage and retrieval.

Agent Frameworks: AutoGPT, LangGraph, CrewAI include built-in context management capabilities.

Context Monitoring Tools: Platforms like LangSmith and Weights & Biases provide visibility into context usage and performance.

MCP (Model Context Protocol): Anthropic’s standard for how agents interact with external tools, emphasizing token-efficient context exchange.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Pitfall 1: Information Hoarding Adding “just in case” information that’s rarely needed but always taking up space.

Solution: Implement lazy loading retrieve information only when needed, not preemptively.

Pitfall 2: Unstructured Context Dumping raw data without organization or formatting.

Solution: Structure information in tables, JSON, or clear hierarchies that models can easily parse.

Pitfall 3: Ignoring Token Costs Treating all tokens equally when some are exponentially more expensive (very long contexts, frequent calls).

Solution: Monitor token usage closely and optimize high-frequency, high-cost operations first.

Pitfall 4: Over-Reliance on Summarization Using LLM-powered summarization for everything, creating token-expensive preprocessing steps.

Solution: Use cheaper trimming and filtering for obvious cases, reserve summarization for critical information.

Pitfall 5: No Measurement Building context strategies without measuring their impact on performance.

Solution: Implement evaluation pipelines that measure task success rate, latency, and cost across different context strategies.

The Future of Context Engineering

As we move through 2026 and beyond, several trends are shaping the future of context engineering:

Longer Context Windows: Models are expanding context windows (some experimental models now support 10M+ tokens), but context rot remains a challenge even in these systems.

Recursive Language Models (RLMs): New architectures that explicitly support hierarchical context management, allowing models to make sub-calls with isolated contexts.

Agentic Context Engineering: Systems where agents themselves manage and optimize their own context, learning what information to keep, summarize, or discard.

Context Compilation: Tools that automatically analyze application requirements and generate optimal context management strategies.

Multi-Modal Context: As models become more multi-modal, context engineering expands to include image, audio, and video management alongside text.

Key Takeaways

- Context engineering has replaced prompt engineering as the critical skill for building production AI systems.

- Context is everything the model sees at inference time not just the prompt, but retrieved data, conversation history, tool outputs, and environmental state.

- The four core strategies are externalization, summarization, trimming, and isolation—used individually or in combination.

- Context rot is real: More context doesn’t automatically mean better performance; focused, relevant context outperforms bloated, unfocused context.

- Dynamic construction is essential: Context should be built on-the-fly for each task, not templated statically.

- Measurement matters: Without evaluation frameworks, you can’t know if your context engineering strategies are working.

- Tools are part of context: Well-designed tools that return token-efficient information enable better agent behavior.

- The shift is fundamental: As AI applications become more sophisticated (agents, long-running workflows, complex reasoning), context engineering becomes the primary determinant of success or failure.

Conclusion

Context engineering represents the maturation of AI development from experimentation to engineering discipline. Where prompt engineering asked “how should I phrase this?”, context engineering asks “what environment should I create for the model to succeed?”

This shift reflects the growing sophistication of AI applications. Simple tasks might still work with clever prompts, but production systems AI agents handling customer support, software development assistants, research tools, creative copilots require thoughtful context architecture.

The good news: the principles and strategies outlined here provide a solid foundation. The challenge: context engineering requires continuous learning, experimentation, and refinement as models evolve and application requirements grow.

For developers, engineers, and teams building with AI in 2026, investing in context engineering capabilities isn’t optional it’s the difference between AI systems that work reliably in production and those that fail unpredictably despite having access to powerful models.

The era of context engineering has arrived. The question isn’t whether to adopt it, but how quickly you can master it.

Have you encountered context-related challenges in your AI projects? What strategies have worked for you? Share your experiences and questions in the comments the field is still evolving, and practical insights from builders are invaluable for the community.

Leave a Reply